Looking for He Guizhen

Chapter 5 – Chongqing 重庆

In November 2012, I went back to Wushan.

As soon as I arrived in Wushan, I called him to learn he had actually moved to Chongqing. I took another bus and went back to Chongqing to see him.

Day 1

I went to a market near the Chaotian Men (朝天门) to see him. It was a lazy and sunny Saturday afternoon in November. Mr. He was standing in front of the building waiting for me.

Not long after we met in Wushan, Mr. He and several of his Laoxiang (fellow villagers) had decided to come to Chongqing to start businesses. Mr. He had experience in trading antiques and souvenirs. In the 1980s, after China’s economic reforms, the Three Gorges area was flooded with tourists with money to spare for souvenirs. Mr. He was selling crafts and antiques to the tourists along the river. He was making a decent income back then according to his description.

In September 2011, Mr. He Guizhen moved to Chongqing with a few Laoxiao (fellow villagers) to look for work and business opportunities. By Nov 2011 when I revisited him, He was trading antiques in a market in Chongqing. - Chongqing, China, Nov 2012

We went into the building and walked to the spot he rented to sell antiques over the weekends. The market reminded me of my college years in Chongqing during the late 1990s. The interior of the market had stayed the same – bare concrete floor, the bottom half of the walls were painted green and the paint was peeling off from the wall and ceiling. However, it looked more depressing. The markets in Chaotian Men had been packed when I was in college. People came to buy cheap but chic clothing, pirated Video Compact Disks and computer games. It was one of our favorite destinations during the weekends.

In September 2011, He Guizhen left his daughter and wife behind in Wushan and joined a group of Wushanners to go and sell antiques on a flea market in Chongqing. - Chongqing, China, November 2012

The antiques that Mr. He Guizhen was trading normally included small and low value items such as the small jade bowls, stamps, necklace, etc. - Chongqing, China, November 2012

It was very common for the vendors to have the entire family working in the market including the babies. The older sister was helping the parents to take care the baby sister. -Chongqing, China, November 2012

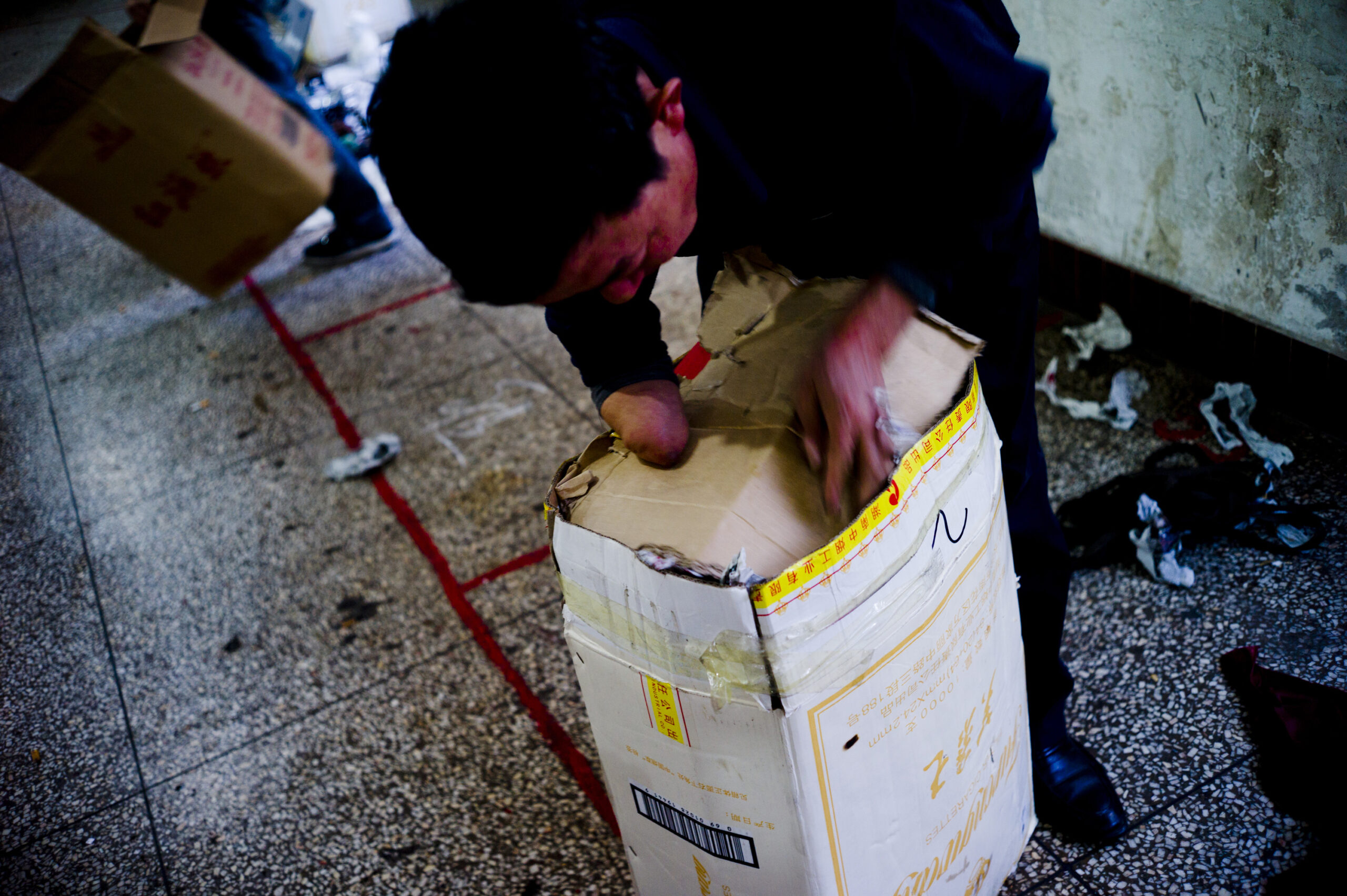

After a couple of hours trying to sell antiques, Mr. He started to pack his stuff into a cardboard box and was ready to leave. I followed him to take a bus back home. He rented a room in a residential building. The room appeared very basic and bare. One side of the wall actually was the aluminum garage rollup door which indicated what the space had been before. Mr. He told me that his daughter’s high school provided her boarding, so he was able to leave Wushan for Chongqing to work or start a business.

For dinner, I invited him for hotpot. We found a place nearby and the dinner went on into the night. Around 7pm, the customers started to pour in while many were waiting outside. Mr. He said to me, “I can’t believe people are waiting for me to finish my dinner.” I was confused and asked why. He told me that they – he and his family as well as the villagers – rarely ate a meal at restaurants. Mostly they would get takeout to eat if they were not cooking at home. In the 1990s, Mr. He and his fellow villagers started traveling to downtown Wushan to sell produce to make some cash. The restaurants in Wushan didn’t allow Mr. He and his fellow villagers to eat in, and forced them to stand or eat outside the restaurant. In order to save money, they always ordered rice with soup to wash it down. Because they spent very little, the restaurants didn’t think they deserved seats and felt their presence would affect the business. Not only did the unfairness shock me, it was even more painful to imagine Mr. He and his fellow villagers just quietly complying and the effect it had on them for decades.

The hotpot restaurant became very crowded at night. Many people were waiting outside for the available seats. -Chongqing, China, November 2012

Day 2

I went to the market the following day. Everyone was engaged in their own business. I was hanging around hoping not to miss anything that Mr. He and other vendors were doing.

The real excitement started around lunch time. It was the time to take a break and legitimately not worry about business matters. Mr. He and I went to an alley to buy lunch. This was before Alibaba and Meituan delivery services and it was exciting to see how the meals were prepared, to order the meals from the gigantic menu hanging on the wall, and to see the crowd eating on the outdoor tables. It was back to my college years when, during lunch and dinner time, the narrow alleys outside the campus were filled with tables, stools as well as the smoke and smell of frying chilly pepper.

We went back to the “trading” floor with a few dishes as lunch was shared with the other Laoxiang. Sitting on the low stools and drinking beers with the flimsy plastic cups reminded me of lunch at a villager’s home in Jingzhou, Hubei Province where Mr. He and his family spent two years.

The atmosphere became relaxed after lunch. Mr. He and his Laoxiang gradually started to pack up their wares and prepare for the trip to Henan to shop for more antiques. Before heading to the bus station, Mr. He and I went back to his room. He was already packed – a large bag for the things to be bought and a plastic shopping bag with his toothbrush and a bottle of liquor.

Mr. He Guizhen was leaving for Nanyang, Henan province to buy antiques. A bottle of hard liquor and toothbrush are his usual carry-on and only luggage. - Chongqing, China, November 2012

A motorized tricycle brought us to the bus station. Mr. He’s friends were already there waiting for us. The station was filled with passengers. Back in 2012, the high speed train was not yet an option in the region, plus the bus was a more economical choice for travel. With his friends, Mr. He pushed through the crowd to board the bus. A little while after, a big blue bus with a plaque of the destination – Nanyang, (a town in Henan province) behind the front windshield came out from the garage. Mr. He opened the window by his seat, waved to me and said bye-bye, the bus accelerated and disappeared into the traffic.

Mr. He Guizhen sticked out from the bus’ window to say bye-bye. - Chongqing, China, November 2012

I was standing at the plaza in front of the station for a little while. Compared to my first experience at this sunken plaza in front of the bus and train station back in 1994 upon my arrival in Chongqing to attend the college, the plaza appeared much more humane and friendly. There were commercials and designed landscape elements to break down the overwhelming feeling to enter the city with 10 million people.

It was the last time I saw Mr. He Guizhen. Four years later, I called Mr. He as I was preparing a grant proposal to see him again. It was disappointing that I did not get the grant, but I was happy to hear from the phone call that He Qiong, Mr. He Guizhen’s daughter, had attended a college in Chongqing. She was the first one in the family to go to college.