The Friction of Everyday Life

Survey 3 – The Opportunities

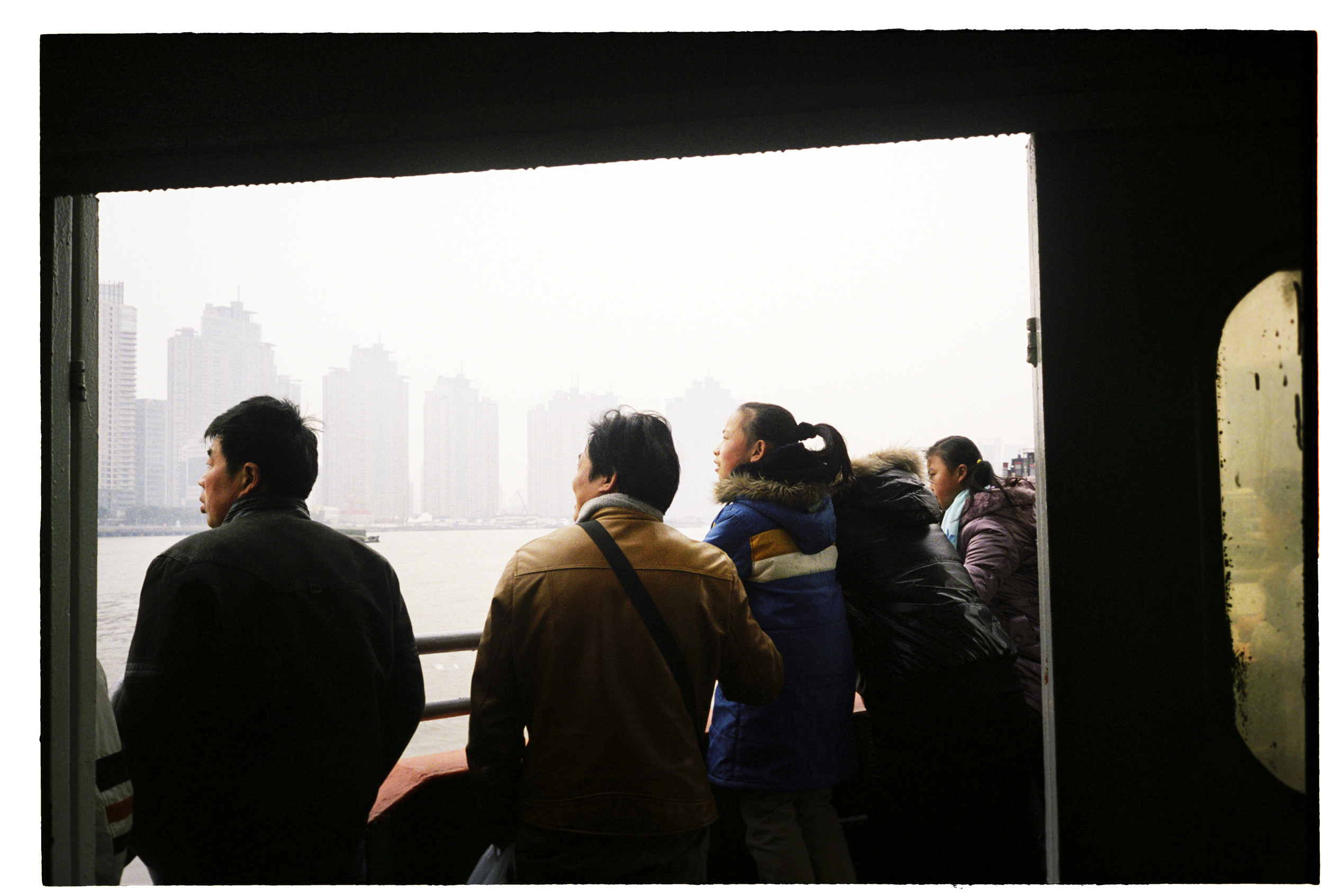

It was January 2010, almost time for the Chinese New Year. I was on my last field trip to China. Walking the streets of Shanghai, I started seeing long lines outside the train ticket offices across the city. It was before a time when almost everyone had a smartphone. People had to physically go to the offices to buy tickets

A month prior to Chinese New Year, people were waiting to purchase train ticket to go back hometown. Shanghai, China, January 2010

The lines reminded me of a photograph I had taken in November 2009 of a group of young people standing on the sidewalk outside the long-distance bus station. They stood tightly together. None of them looked very excited but rather anxious. This was before everyone had a cellphone, much less a smartphone. To the far left of the group, a few people gathered around a girl who was speaking on a cell phone. At the other end, a fashionably dressed man stood at a distance from the group and was speaking on the phone as well. This was evidence that the group had just arrived in Shanghai from the countryside and was waiting to be picked up to go to work. The man on the phone must have been a recruiter. It took me years to understand this photograph. Now I wonder where they would be working and whether they would take the train to go home for the Chinese New Year just three months later.

A group of young people just arrived in Shanghai via long distance bus and were waiting for being picked up. Shanghai, China, November 2009

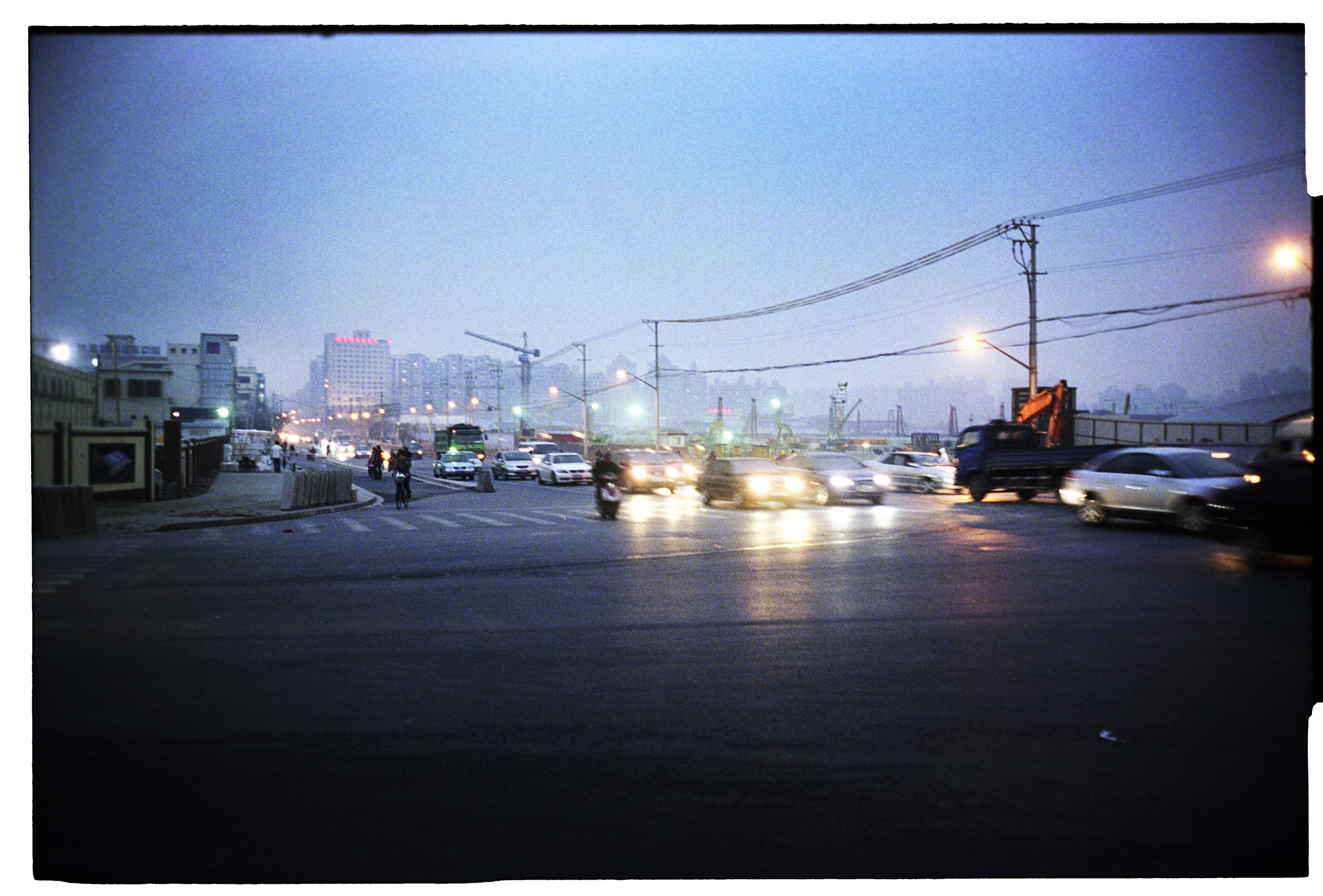

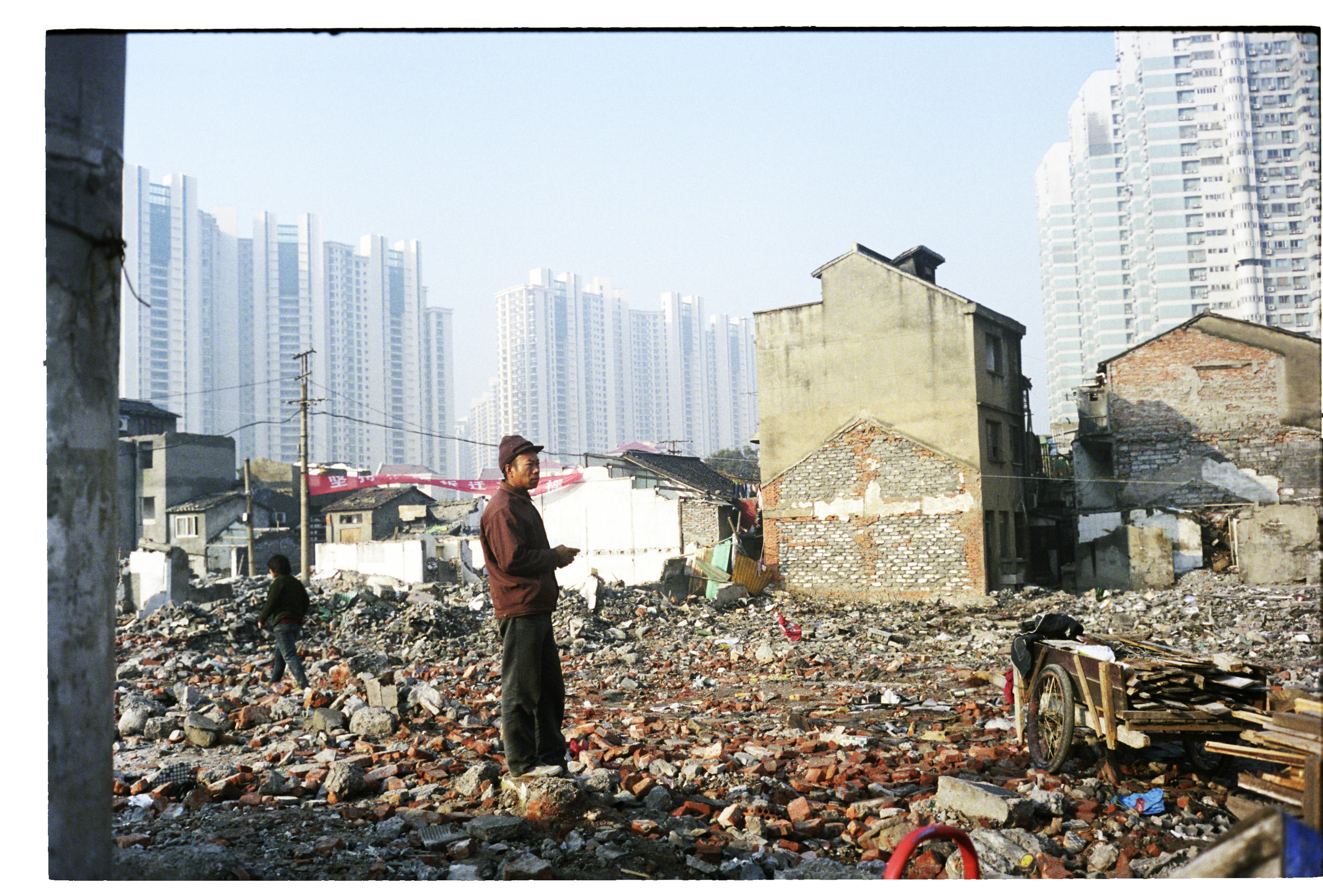

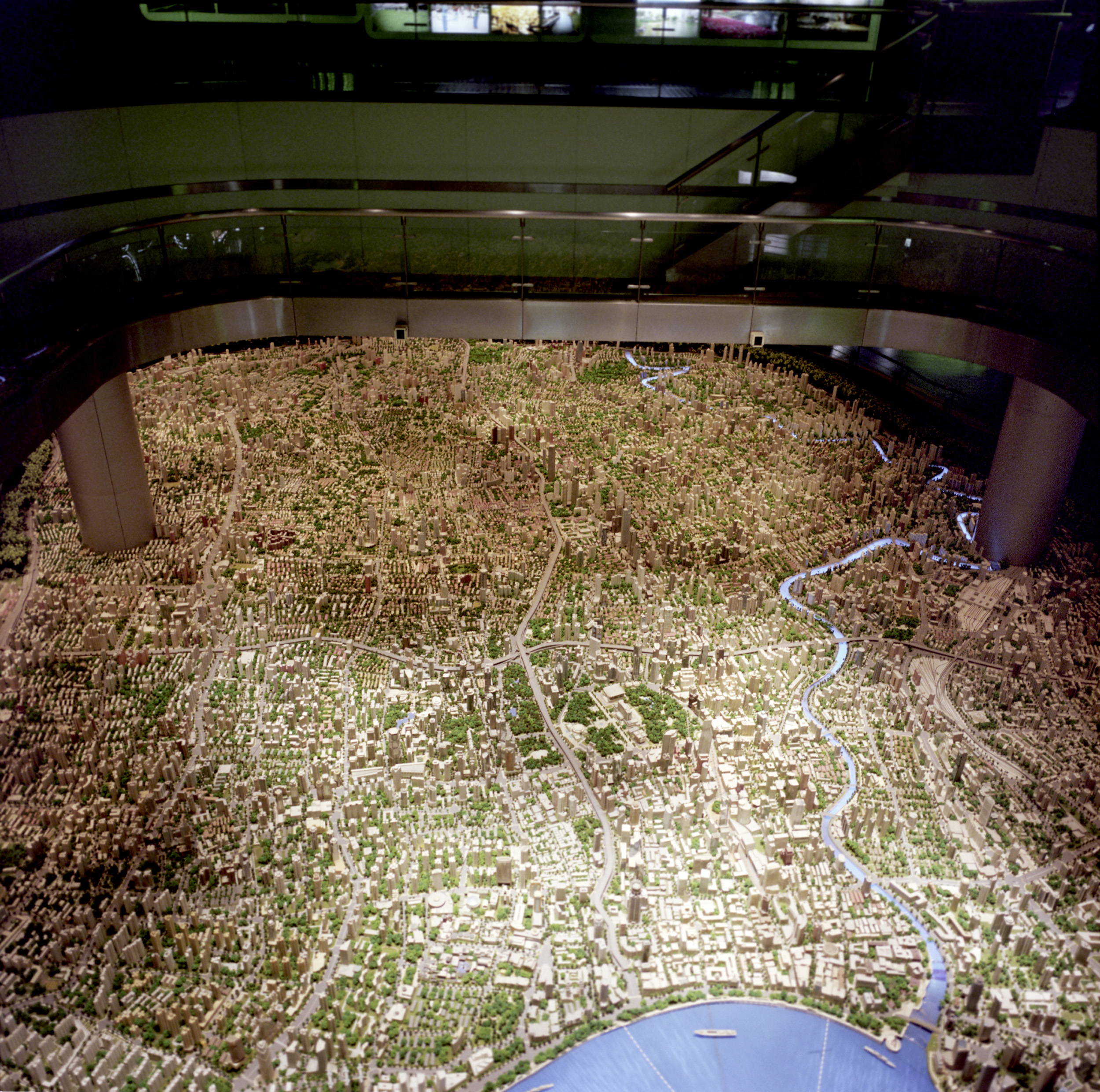

Despite Shanghai’s established status as China’s largest metropolis for around two centuries, the city has been experiencing an unprecedented overhaul since the 1990s. The new Shanghai is literally being built by migrant workers. Yet, a migrant family is packed into a single room at the seafood market where they worked. Millions of square meters of new apartments have been constructed, but many natives of Shanghai were stuck in virtually uninhabitable housing at the center of the city.

The Tongchuan Road Seafood Wholesale market was one of the largest seafood market in Shanghai before it was demolished. Majority of vendors were migrants. The utilized the small room for living, where they could also take care of the business. It wasn’t uncommon as housing cost was high. Shanghai, China, January 2010

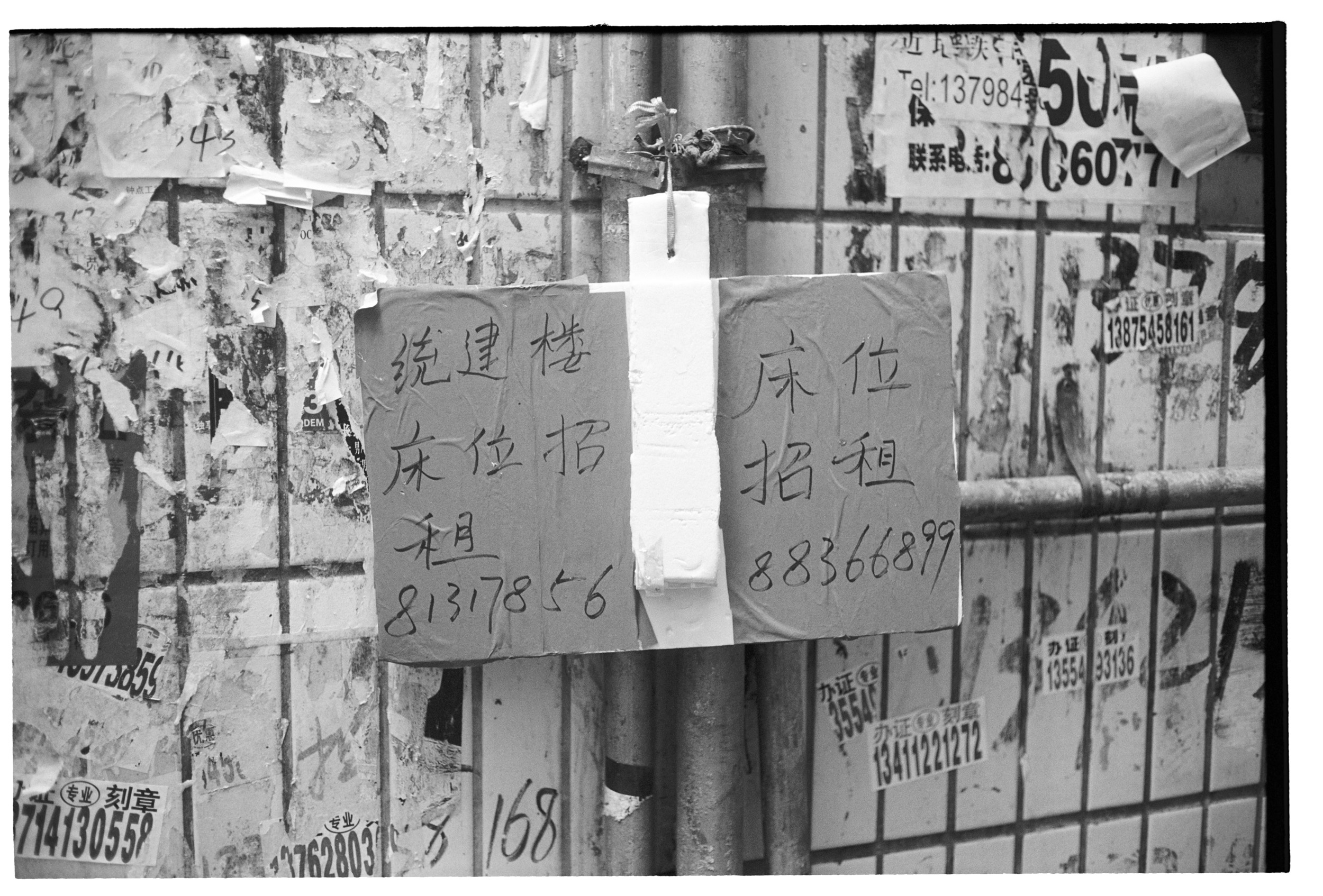

In March 2009, I visited Ms. Zhou at her apartment in an urban village in Shenzhen. She shared the apartment with another girl. Ms. Zhou was from a village in Hunan province. She went back home at least twice a year – to help with the planting of the crops and for Chinese New Year. By 2009 she had been in Shenzhen for almost a decade, but she knew her status was temporary.

Ms. Zhou came to Shenzhen from a rural village in Hunan Province when she was 17 years old. She was pay RMB 1,000 Yuan to share a two-bed apartment with a roommate. The apartment was in one of the urban villages. She considered the rent was affordable but was not sure what would happen in the near future as many urban villages in Shenzhen were demolished. - Shenzhen, China, March 2009

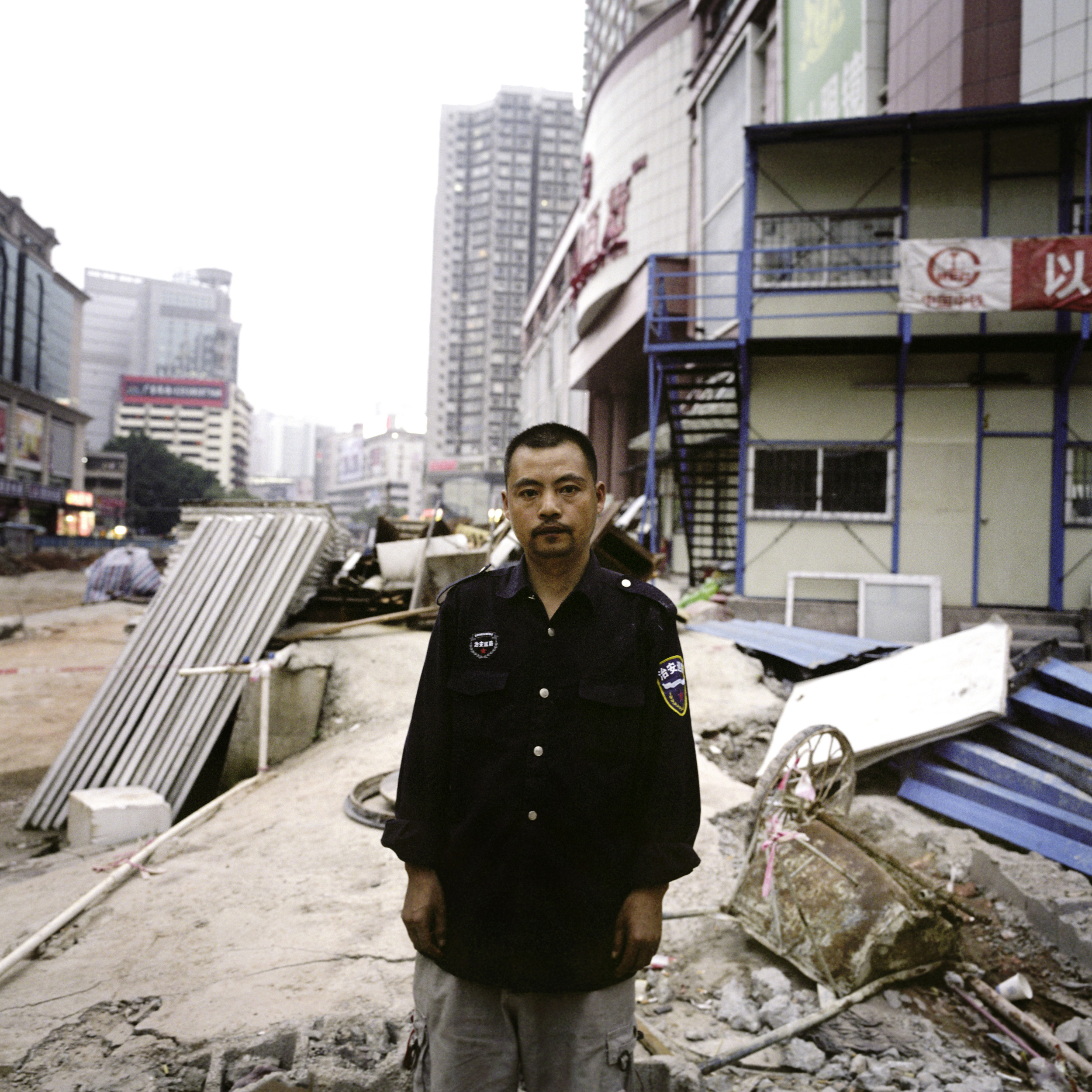

An official in Yumin Village, another urban village in Shenzhen, told me stories of how villagers become prosperous by utilizing the allocated land to develop real estate. He was proudly standing in front of the flag of the Communist Party of China.

The official of Yumin Village in Shenzhen. Yumin Village was one the first few villages in which the villagers’ income exceeded RMB 10,000 yuan during the 1980s. Yumin Village is one of the first urban villages in Shenzhen. The original villagers had been able to leverage the allocated land to create real estate projects. Shenzhen, China, March, 2009

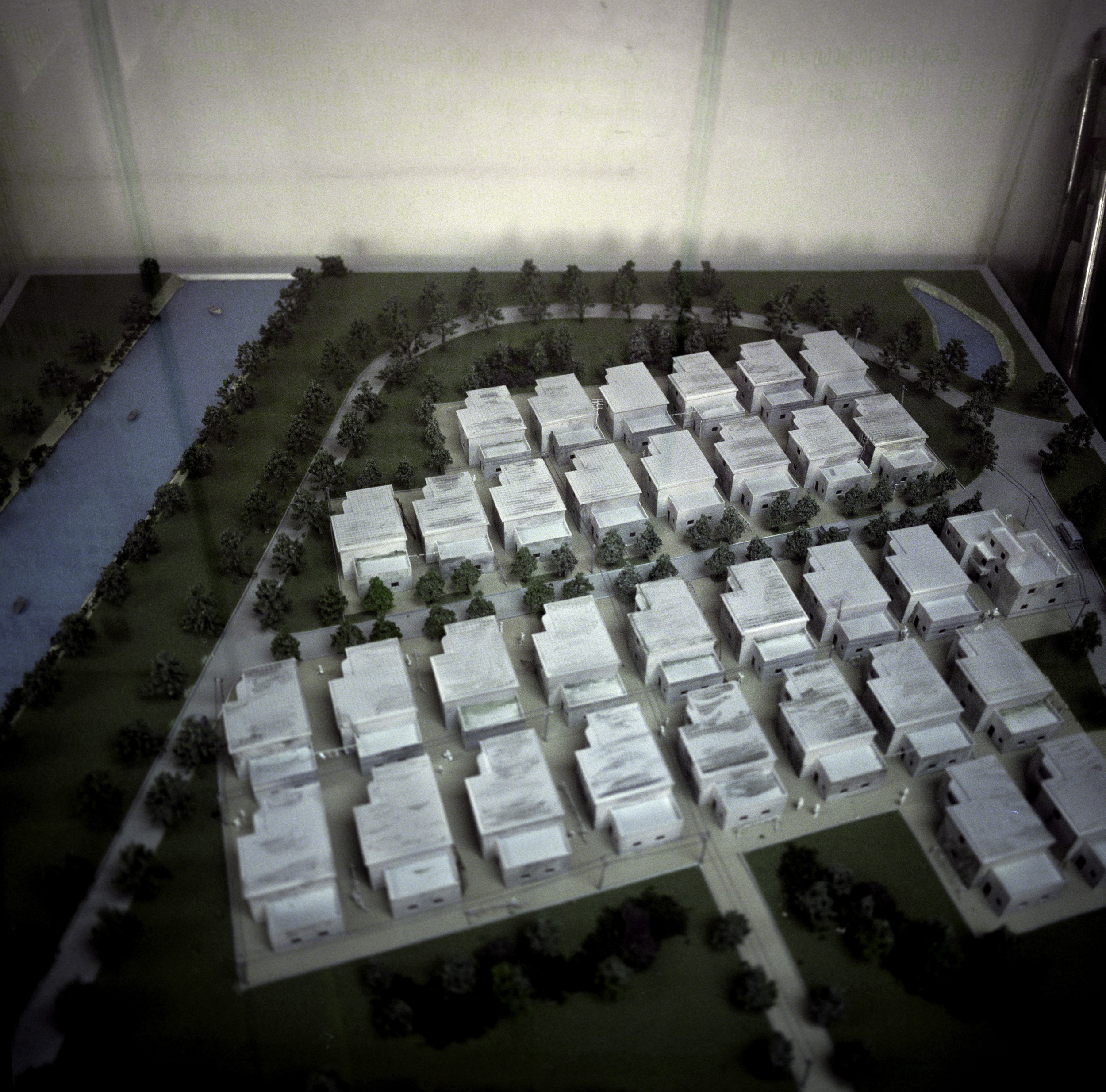

A scaled model of Yumin Village in the 1980s. Yunmin Village was one of the first few villages in which the villagers’ income exceeded RMB 10,000 yuan during the 1980s. - Shenzhen, China, March 2009

Taking these photographs allowed me to look beyond a specific site and explore its context, which was essential to understanding the mechanisms of how and why the issues I was interested in emerged. They are a cross-section looking into many aspects of the cities.

I want the viewer to consider these images as an invitation for dialogues and leave room for the coexistence of overlap and disagreement.